On Censorship: Banned Books Thought Piece

By A Noise Within

August 23, 2023

By Miranda Johnson-Haddad

Originally published August 21, 2023 by Picture This Post

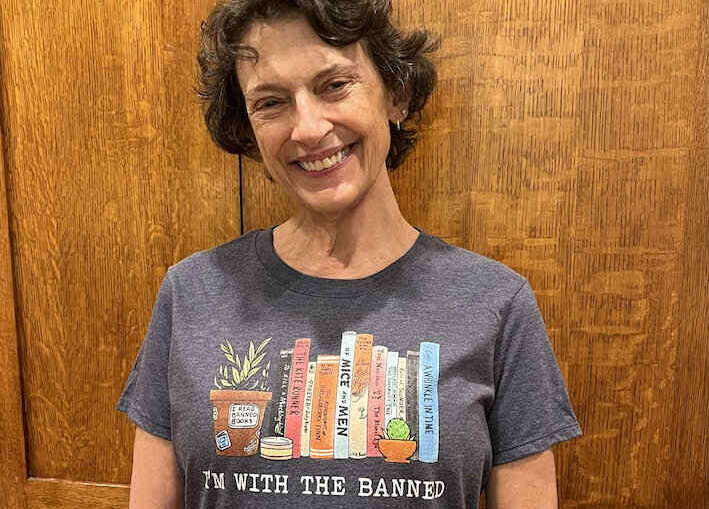

For my birthday this year, my husband gave me a tee-shirt depicting a shelf of eleven banned books, their titles clearly visible on their brightly colored spines, with the caption “I’m with the banned.” The inspiration behind his gift was that one of the titles shown is Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. As the Resident Dramaturg at A Noise Within Theatre in Pasadena, CA, I’ve been working for months on the upcoming production of Lydia Diamond’s 2007 dramatic adaptation of the novel. I knew going in that Morrison’s first novel, written in 1970, has been challenged or banned pretty much continuously ever since its initial publication. But as I began working with director Andi Chapman on the production (which runs from August 27 through September 24), I found myself thinking about not only what accounts for the continuing bans of a book written over fifty years ago, but also about what artists owe to the project of keeping this and other contested works alive and accessible in the face of virulent opposition.

As a well-established classical repertory company, A Noise Within has been actively engaged for several seasons in redefining what constitutes classic theater, and I’m deeply committed to this ongoing mission. But I’m also acutely aware of the tenuous position in which most American theaters find themselves these days. The pandemic dealt a body blow to numerous performing arts venues all across the country, and most of them have yet to see their audience numbers—let alone their donor base (in the case of nonprofit theaters)—return to pre-pandemic levels. For months now, my Inbox has been flooded with articles, opinion pieces, and hand-wringing analyses of why so many theaters in the U.S. are struggling, pausing their season, or shutting down for good. Even such institutional behemoths as the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, the Mark Taper Forum (part of Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles), and the New York Public Theater have had to retrench significantly (**A Crisis in America’s Theaters Leaves Prestigious Stages Dark, The New York Times). And while the dramatic adaptation of a novel as powerful as The Bluest Eye certainly constitutes a shining example of an updated definition of classic theater, presenting it in the current cultural environment is a risky enterprise. Are theaters artistically and perhaps even morally obligated to present these controversial works, even at the risk of going under, and thereby handing yet another victory to the censors?

Toni Morrison’s books have always been among the most frequently challenged and banned in the country, even before the current insanity, and The Bluest Eye isn’t the only title of hers that regularly lands on banned books lists. The Bluest Eye isn’t even the oldest book to appear on these lists; that honor belongs to Mark Twain’s 1876 novel Tom Sawyer (although Twain seems to be in danger of being unseated by William Shakespeare, given recent developments in some Florida school districts). According to the American Library Association**, which has been tracking book banning for over thirty years, the reason typically given for challenging The Bluest Eye is that the novel is perceived as being “sexually explicit.” But let’s be real: that’s not the reason behind the censorship attempts. For evidence that the sexual content claim is a red herring, we need only consider the fact that the incidents of banning The Bluest Eye become more frequent with each passing decade; the novel has moved steadily up from the 34th most banned book in 1990-1999, to the 15th in 2000-2009, to the 10th in 2010-2019 – all decades during which American tolerance for sexual explicitness in literature (and everything else) increased significantly. And this trend continues: in 2022, The Bluest Eye came in at number three. It was the oldest book (by almost thirty years) among the top six, and the other five were all banned primarily for LGBTQ+ content or themes.

It’s true that an act of sexual violence lies at the heart of The Bluest Eye, and it’s also true that Morrison doesn’t shy away from describing it. But the description is far less graphic than what appears in many more recent novels, including some that are considered to be literary works of major importance. The horror of that moment in The Bluest Eye is both individual to the character suffering through it and also epic in its overarching tragic significance. There is nothing gratuitous about what happens, or about Morrison’s description of it. In Diamond’s thoughtful adaptation, the characters describe what occurs but do not perform it. Diamond made this choice not out of squeamishness, but because she believed that enacting it would cause viewers to fixate on the individual horror and overlook Morrison’s intention in the novel — an intention that Diamond (who worked with Morrison on the play) contends is to depict the damage done by “crippling societal racism.”

Diamond’s choice brings us back to the question of what accounts for these steadily increasing objections to a fifty-three year old novel. It’s clear that The Bluest Eye is banned because it addresses the evils of ongoing systemic racism in the U.S., evidently such an unsettling topic for significant numbers of our fellow citizens that it can’t even be named, let alone discussed. But that’s not the primary reason why The Bluest Eye is increasingly banned. Significantly, The Bluest Eye addresses racism from the perspective of the novel’s Black characters, and without reference to what Morrison famously called the “white gaze.” In the worlds of Morrison’s novels, it’s not that white people are erased, or that they don’t matter; what’s truly radical—and, apparently, threatening—is that Morrison was profoundly uninterested in writing about white people. One early (and now infamous) review of both The Bluest Eye and Sula (Morrison’s second novel, written in 1973) laments that “Morrison is far too talented to remain only a marvelous recorder of the black [sic] side of provincial American life.” The reviewer adds that if Morrison could expand her subject matter – presumably to include more about white people and their experience — she would be able to “take her place among the most serious, important and talented American novelists now working.” Morrison remained consistently unmoved by such myopic assessments (assessments that only served to prove her point about white gaze). She kept writing about what interested her, eventually writing herself all the way to a Pulitzer Prize (for Beloved, written in 1987) and the Nobel Prize for Literature (awarded in 1993).

So what is the role that theater artists are called upon to play amid the current controversies? It’s now a matter of both anecdote and record that when theaters attempt to shake up the classical canon, whether by the specific plays selected for performance or by the interpretative choices around a production of an enshrined author, from Shakespeare to Tennessee Williams, many of those theaters get at least some degree of negative pushback. (Think of the outrageous abuse to which Nataki Garrett was subjected when she took over as the Artistic Director of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival**). The national reckoning with racism that began in the summer of 2020 after the murder of George Floyd quite rightly did not give arts institutions a pass. The “We see you, white American theater” letter** and subsequent activist movement forced many theaters to take a hard look at themselves and admit that they were falling far short in practice of the principles and values their leadership, and their Boards, espoused in theory.

The theaters that are truly committed to making a difference and to making amends understand that this institutional awakening represents a call to action, and their leadership has embraced our current cultural moment as an opportunity. Now it’s time to take a stand with a quantifiable cost. As I write this, the largest public interest law firm in Los Angeles, Public Counsel, has sued the Temecula school board on behalf of a group of plaintiffs that includes students, teachers, and parents for banning the teaching of Critical Race Theory in middle school and high school, which effectively means banning books, including – you guessed it, Reader – The Bluest Eye. The leadership at A Noise Within promptly responded to news of this lawsuit by inviting the plaintiffs to attend a performance, with the costs completely subsidized by ANW.

Will ANW get some flack for this? Probably, but I predict that they’ll receive far more supportive responses than negative ones. But even if this doesn’t prove true, it’s the right thing to do, not just socially and morally, but artistically. As I like to say (to my theater colleagues and to my kids), art is meant to move us. We all have an obligation to support art however we can, no matter how personally triggering or financially imprudent it may be to do so. Morrison wrote in the foreword to the 2007 edition of The Bluest Eye, “[W]atching cultural exorcisms debase literature, seeing oneself preserved in the amber of disqualifying metaphors – I can say that my narrative project is as difficult today as it was [in 1970].” Morrison did the brave, hard work. The least that the rest of us can do is to carry it forward and not allow the bullies to win.

For more information about the upcoming production of The Bluest Eye or to purchase tickets, visit the A Noise Within website.

** Please read the various references sited by the author—

A Crisis in America’s Theaters Leaves Prestigious Stages Dark, The New York Times

Banned & Challenged Books, American Library Association

Nataki Garrett to Leave Oregon Shakes Amid Emergency Fund Drive, American Theatre

We See You White American Theater letter

Editor’s Note: Read related stories from Picture This Post, and beyond!

Read other A NOISE WITHIN stories here

Join the Picture This Post Campaign to Stop Censorship of Thought and Expression