Q&A with Dorian Director Michael Michetti

By A Noise Within

October 22, 2018

Many audience members had burning questions in their minds after seeing A Picture of Dorian Gray, and Director Michael Michetti has graciously taken the time to give us more insight to his adaptation and production.

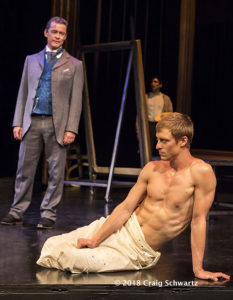

Q: How did you decide the portrait should be full-length and nude? Was it like that in the book?

A: There aren’t many passages in the novel that describe the actual painting, other than the description of Dorian’s beauty, and its later decay. The first reference is to a “full-length portrait of a young man of extraordinary personal beauty,” and Dorian refers to it as “a life-sized portrait.” The text doesn’t say that the portrait is a nude, and I’m sure it wasn’t Wilde’s intention that it is.

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t textual support for that choice. I point to these two references:

- Basil describes his art, influenced by Dorian, as having “all the perfection of the spirit that is Greek.”

- Lord Henry, while the portrait is being painted, imagines a time when “we would forget all the maladies of mediaevalism, and return to the Hellenic ideal.”

These two quotes are particularly interesting in correlation to the Aestheticism Movement, of which Wilde was a prominent proponent. In the visual arts, the Aesthetics predominantly embraced the Pre-Raphaelites, who were painters heavily influenced by the medieval period as a stylistic model. And the Pre-Raphaelites, like other Victorian painters, painted very few nudes. However, Wilde had studied the Greeks at Trinity and Oxford (as the character of Lord Henry would have), and Wilde was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy and art, or “the Hellenic ideal.” Greek art typically depicted the male form as nudes, the nude male body being seen as the pinnacle of perfection.

There are also metaphorical resonances that are accentuated by making the portrait a nude. As Dorian is innocently posing, Harry begins to describe to him his theory of living life for pleasure and in hedonistic pursuits, of the sins of the body, and of yielding to temptation. Harry has caught this innocent young man at a moment when he is entirely exposed and vulnerable. Then, as Harry is describing to Dorian “passions that have made you afraid, thoughts that have filled you with terror, day-dreams and sleeping dreams whose mere memory might stain your cheek with shame…”, Dorian interrupts with, “Stop!… Don’t speak. Let me think. Or, rather, let me try not to think.” And in the staging of the play, this is the moment when Dorian wraps himself in a length of muslin, hiding his nakedness. As in the story of Adam and Eve, when Dorian begins posing for the portrait he is not ashamed, but after “tasting of the fruit of knowledge” his eyes are opened, and he realizes that he is naked.

In addition, there are theatrical advantages to the nudity. There is no question that nudity has a primal, visceral impact on stage. It makes people feel something, whether that’s discomfort, aesthetic appreciation, embarrassment, desire, jealousy, attraction… As Dorian is described in the novel, his beauty has a similarly visceral impact on all those who encounter him. But I’m afraid we’ve become somewhat inured to beauty, especially on stage where we’re so accustomed to beautiful people. The challenge then becomes how to give the audience that emotional sucker-punch, so they too feel the emotional impact of Dorian’s beauty, rather than just to understand it intellectually. For many the nudity accomplishes that.

Finally, so much of what was considered shocking in Dorian Gray by Victorian standards has become accepted, and even mundane, 128 years later. The nudity gives the play the same jolt of danger that the novel would have had when it was first published.

Q: Why was portrait’s evolution left to one’s imagination unlike the movie I saw in the 1940’s?

A: I chose to depict the portrait with an empty frame for three reasons:

First, each time I’ve seen an adaptation of this novel (on screen or stage), I know I’m supposed to be frightened or repelled when I see the aging, corrupted portrait, but I never am. In fact, my reaction is usually to laugh. The literal portrait can never, for me, quite achieve the emotional effect it’s intended to have.

Second, the gothic horror aspects of Dorian Gray are, for me, the least interesting. There’s obviously a supernatural component to the story, but for me the psychological portrait is much more interesting than the actual potrait. This is not the story of a rotting painting; it is the story of a rotting soul.

And third, the theatre is a medium of the imagination. By using the chorus to represent the conscience of the person viewing the portrait, repeating the “prayer” that Dorian made while first viewing the painting, and by seeing the reactions of the viewer, our imaginations can fill in the empty frame. I’m fascinated by the idea that each audience member will paint their own portrait in their mind’s eye. To quote Wilde, “I said in Dorian Gray that the great sins of the world take place in the brain, but it is in the brain that everything takes place.”

Q: Why did you have the monologue at the beginning of the second act?

A: One of the most challenging sections of the novel to dramatize was the chapter that indicates the passage of 18 years time. In the book, this chapter primarily chronicles Dorian’s acquisition of beautiful things and hunt for beautiful sensations, all described in sensual prose. So I chose to create a sequence that depicts the ruin that Dorian brings to those around him, as well as his insatiable pursuit of pleasure, in which there are four elements:

- The first is excerpts of the text from that chapter. This recitation is not the primary narrative focus of the scene, but rather almost an accompaniment motif for the action.

- The second is the presence of the three characters (aside from Dorian) who span this period in the narrative (Harry, Basil and James Vane), as they apply theatrical age make-up to the side of the stage, depicting the passage of 18 years and the ravages of time on all but Dorian.

- The third is the gradual reveal of the “assemblage” of furnishings and objets d’art at the back of the stage, which becomes a visual metaphor for the material excess in Dorian’s life, as well as the disorder and overindulgence of his mind and soul.

- Against all this, and the real narrative drive of this sequence, is the series of dances (choreographed by John Pennington) which depict Dorian’s encounters with various people as he uses each of them for his own pleasure and material gain, and then discards them, broken and depleted.